Bottled

Chapter 1.

Martin’s Sunday began much like any other. Everything proceeded absolutely as normal, down to the pleasant breeze that met him on his way to the large glass deposit bin. The cool air filled his nose and lungs, pushing out the last webs of sleep.

At the bin, though, things became strange.

The fundamental process was no different than usual. Walk up to the bin. Put down the cardboard box full of glasses to be placed in the bin. Select a nice large bottle from the box. Pick it up with your fingers — as few as possible, to minimize points of contact and contamination — and place the glass bottle up against the hole in the bin. Push the bottle just hard enough to get over inertia and the rubber covering the hole, to send it sliding and then falling down into the bin where it lands with a satisfying “OW!”

Then repeat the process. Select the next bottle. Pick it up—

“OI!”

Martin paused. Upon reflection, he realized that he probably should have registered that his glass bottles didn’t usually shout in pain when landing in the bin. Actually, they never did that. Perhaps he had misheard? But then again, the second shout...

As Martin deliberated, the voice spoke up again.

“HELLO?”

It was a distinctly unfriendly hello. About as unfriendly as you might expect from someone — something? — who had just had a glass bottle dropped on their head.

“Hello?” Martin replied.

“What was that for?” The Voice asked.

“Um,” Martin responded.

“Not got much to say, have you?” The Voice said. “Feeling embarrassed, are we?”

“Oh,” Martin said.

“Come on then, big boy,” The Voice said. “Don’t get shy now. Why’d you throw a fucking bottle at me?”

“Sorry,” Martin replied.

“About fucking time,” The Voice said. “Was that so hard?”

“Are you OK?” Martin asked.

“No, I’m not OK,” The Voice said. “You woke me up. My head hurts. There’s a dirty wine bottle in my lap.”

“Sorry,” Martin said.

“Apology accepted,” The Voice said. “This wine bottle, not.”

The wine bottle launched out of the glass deposit bin receptacle. It clattered down on the asphalt surrounding the bin, narrowly missing Martin and his cardboard box; the bottle rattled and span on the ground, but didn’t break. The noise was abrasive and out of place among the quiet sounds of a neighborhood early on Sunday morning.

Martin winced, waited, but that seemed to be it. He looked down at his box of glass. Put down the bottle he had been in the process of picking up. It clinked against the other glasses in the box.

“Don’t even think about it,” The Voice said. “Fuck me, have you got a whole bag of these?” Martin cringed, frozen in place.

“What are you, some kind of psycho?” The Voice asked. “What did I do to you?” “Look,” Martin began, “I don’t know why you’re in the glass deposit bin—”

“Is that seriously what I look like?” The Voice interrupted.

“Sorry?”

“What did you say — glass deposit bin?” The Voice was scathing. Vicious. Disbelieving.

Martin took a step back and re-appraised the situation in front of him. The glass deposit bin looked the same as it always did. It was large and gray. There was the circular receptacle in the middle, lined with faded black rubber. On the front was a sign with some instructions. Yes, the sign was quite clear. This receptacle was for glass. In fact, that was the title of the sign: “GLASS RECYCLING.” A helpful illustration underneath this title demonstrated the various types of glass items that were acceptable. Wine bottles were among them.

Before Martin could formulate a response, The Voice spoke up again.

“What’s your name?”

“What?” Martin wasn’t expecting to have to answer that question. He had been so focused on evaluating whether the glass receptacle bin had not, in fact, changed since last Sunday, that being suddenly thrown onto another topic of conversation short-circuited him.

“Jesus Christ, mate,” The Voice said. “Not the sharpest shard in the glass deposit bin, are we? Ha. Ha-ha.”

The Voice snickered a few more times as Martin attempted to gather his thoughts.

“Now look here,” he tried again.

“Yessir!” The Voice mocked.

“This is a glass deposit bin,” Martin said. “There’s a sign right here that says as such.”

“Sign?” The Voice said. “I don’t see a sign.”

“It’s on the outside of the bin,” Martin said. “It’s right here.”

“Whatever you say, boss,” The Voice said. “Sure, there’s a ‘sign’ that says this is a ‘glass deposit bin.’ Alright.”

“Right,” Martin said. “So I’m going to go ahead and put my glass in, then.”

“Go ahead,” The Voice said. It did not sound genuine.

Martin bent over to pick up the original wine bottle from the ground. He hefted it, agonizing over what to do.

No, he thought. No, no no, come on now. This is the glass deposit bin. You put your glass rubbish inside every week. It gets collected on Monday morning. It doesn’t matter if some schizoid has somehow snuck inside—

Martin started. How had The Voice gotten inside the bin?

Come to think of it, Martin had never noticed an entry point to the bin. Actually, the rubber lining the receptacle seemed to imply that the bin was very much not to be entered. Not by mice, nor rats, and certainly not loud, aggressive hobos.

The bin didn’t have any obvious doors. Martin paced around it, flinching as the wet grass around the back of the bin brushed against his bare ankles. His slip-ons were quickly soaked, as were the too-short hems of his old pajama trousers.

No, there was no handle to indicate a door. As Martin recalled, the bin was emptied mechanically. A large truck pulled up, and a robotic arm lifted the entire bin out of the ground. The bottom of the bin then opened up, dumping the contents out. It was all very efficient.

“I can hear you creeping about,” The Voice said.

Martin flinched. He had not walked stealthily enough.

“No, don’t stop,” The Voice said. “Please, don’t let me stop you. Keep on creeping about. Perv.” “Now, really,” Martin began.

“PEEEEEERVERT!” The Voice screamed. The shout bellowed out of the receptacle as through a megaphone. A couple of nearby pigeons were startled off of the neighboring food bin. “HEEEEEEELP! PEEEEEERVERT!”

Martin fled. Halfway back home, he realized he had left his box of glass. Damn it, he thought. Too late.

Through the driveway, up the steps, into the front door. Martin slammed it behind him and leaned against it, panting. These slip-ons weren’t made for running. They were made for shuffling.

Did anyone see that? Martin thought. He glanced at the antique grandfather clock in the front hall. It read 5:22 AM. That meant it was 5:17 AM. Far too early for people to be up and about. God. What a mess. Martin shook his head, took a deep breath, and slipped off his slip-ons. He walked into the kitchen and started the kettle. Back to the normal routine.

When Sundays were nice, Martin liked to wander down to the corner shop and buy himself a magazine and perhaps an ice lolly. As this Sunday was shaping up to be a real scorcher, he decided to make the pilgrimage earlier than usual.

It wasn’t until he turned right after leaving his driveway that a nasty thought struck him. This wasn’t the way to the corner shop. It was a way, but totally inefficient. He should turn left. Always did turn left.

Unfortunately, turning left would take him right past the glass deposit bin. Martin had never before considered this fact important. But it now made him hesitate.

The sun beat down on his head. He hadn’t put on a hat, and his thinning hair was no protection at all. He felt the sun burning his exposed scalp. Beads of sweat were already forming on his forehead.

Martin shook his head and very firmly turned left. He walked down the road as he always did, making sure to adopt an unaffected look and strictly sticking to a casual pace. When he drew opposite the glass deposit bin, he glanced over. Just to take a look. It looked the same as before. Except—

Hold on. Martin’s cardboard box was there. But it was empty.

Before he knew it, Martin had stopped. He was staring. How did that happen?

Martin looked around. People were about. Someone must have emptied the receptacle for him. God, that’s embarrassing! They probably know it’s mine, too. Now I’m the neighbour who leaves his rubbish for other people.

Martin agonized for a moment, then stopped. He had a stroke of genius. What would he do if he encountered a cardboard box left on the path while walking?

Martin crossed the road, shaking his head and tutting as loud as he could. A few furtive glances to each side confirmed the presence of potential audience members. Who knows how many might be hidden behind window blinds or barely parted curtains. When he reached the box, he peered inside. Totally empty.

Still shaking his head, Martin stomped on the box to flatten it. Once, twice, thrice, until it was squished flat.

“Go on, get it out,” The Voice said.

Martin jumped.

“Satisfying, isn’t it?” The Voice said. Its tone was far friendlier than it had been earlier. “Love stomping up a box, myself. Mum always let me do it when we’d finished our Cheerios. Those fuckers are tough. Or at least they used to be, back when big business actually gavea. shit about the importance of quality packaging.”

Once again, Martin found himself frozen in fear of a voice coming out of the glass deposit bin. As he stood, one foot still on the crushed cardboard, he realized that he had subconsciously been hoping that the morning’s misadventure had been a bad dream. Or perhaps a result of lingering sleepiness. Or possibly a complex prank cooked up by one of the more intelligent specimens in the local youth gang.

Unfortunately, the voice was still clearly here. And now Martin had destroyed his cardboard box. He would have to get a new one now, or figure out some other method of storing his glass and bringing it to the deposit bin. But that box had been the perfect size. It fit in the annoyingly small cupboard below the sink and held just the right amount to account for his weekly glass usage. Replacing it would be difficult, if not impossible.

“Not a yapper, huh.” The Voice said. “Well, it is Sunday after all. I’d still be snoozing right now if some wanker hadn’t woken me up by throwing a fucking wine bottle on my head. Excuse my language. Or don’t. And not that you asked, but it was the second cheapest red from Waitrose. Don’t ask me how I know that. And while you’re at it, don’t tell anyone that it’s actually the cheapest one — they just mark up the price because they know people like that prick will be too embarrassed to buy the cheapest one and won’t be able to tell the difference anyway.”

There was a moment of silence. The pigeons were back on the food bin. One was bobbing its head and flaring its tail at the other rhythmically. This situation was clearly not the work of the local hoodlums. Would Waitrose really do that?

Martin slowly pulled his foot off of the cardboard box. He picked it up and placed it inside the cardboard deposit bin. A part of him tensed, but the voice stayed quiet.

It took a good half hour for Martin, sitting in the parlour, to realize that he had never made it to the corner shop. The heat had only gotten worse. Even with the windows open, the room was stifling.

With a sigh, Martin heaved himself up from the couch and left the house. As he turned onto the pavement, he bumped into Margorie and her dog.

“Oh!” Martin said in surprise. “Hello!”

Margorie squinted at him through a thick pair of glasses. She was old and short, but an imposing, perfect posture made her seem taller. Her dog, on the other hand, was shriveled and twisted. It was a ratty white creature with stained fur around its mouth. The coloured furs glistened in the sunlight and wafted with dog’s breaths. Martin couldn’t maintain eye contact with either of them, so he focused on the left rim of Margorie’s glasses.

“Morning, Martin,” the lady said. “Scorcher, isn’t it?”

“Yes,” Martin said. “Terribly hot. I’m on the way to get myself some refreshment.”

“Good idea,” Margorie said. “Just be careful about what you go for, now.” She prodded Martin in the gut. Hard. He laughed awkwardly.

“By the way,” Margorie continued, “you don’t know who left all that glass by the bin, do you?” Martin froze. He forced himself to maintain his already pained smile. The knot in his stomach tightened.

“A whole box full of glass, just dumped by the bin,” Margorie said, shaking her head. “Awfully inconsiderate.”

“Terribly.” Martin said, his voice breaking. “Um. Terrible.”

“I mean, really,” the woman said. “You’ve already brought your glass to the bin. How hard is it to put it inside?”

“Right.”

“And now it’s gone!” Margorie said. “It wasn’t me, I can tell you that. Nor was it Linda. I’ve just spoken with her.”

“Do you know who it was?”

“Unfortunately not. But I’m asking around, and I have my suspicions.”

“Have you used the deposit bin recently?” Martin asked.

“What? Of course.”

“I mean — have you used it today?”

“No, not today. Why?”

Martin hesitated. Dare he?

“Don’t tell me you think that was me?”

“Oh, no. My apologies, I wasn’t implying anything like that.”

“Then why on Earth do you care if I’ve used the deposit bin recently?”

“No reason,” Martin coughed again. “Just wondering.”

“Right.”

“Anyway, must get going,” Martin said. “Refreshment awaits. Have a nice day.”

Martin stepped around the pair and walked on down the road. He replayed the conversation over. Had he marked himself as a potential suspect? Confirmed pre-existing suspicions? “Pssst.”

Of course, with people like that there was sometimes so helping it. Suspicions would abound. But perhaps he could put in a word with the fellow at the corner shop to get ahead of things. “Psssssssssst.”

Martin stopped. Someone was attracting his attention. But upon looking around, the pavement was absolutely bare, except for Margorie and her dog, who were both walking away from him, and were certainly not making much noise. Which meant the noise was coming from— “PSSSSSSSST,” The Voice hissed.

Martin’s stomach sank. His nerves, already winnowed by the heat, had been seriously tested by the confrontation with Margorie. She was difficult to handle at the best of times. And now the glass deposit bin was beckoning him.

“I know you’re there. The guy who dropped a wine bottle at me.”

The Voice paused, waited. Martin stayed quiet. Sweat rolled down his face.

“Aw, come on. Don’t ignore me now. Listen, if you’re still there, do me a favour, would you? One small thing and the whole bottle thing will be forgotten. Clean slate. Restarting on the right foot. Forgive and let live.”

Oh, fine. Martin crossed the road and stood in front of the glass deposit bin. Even a few feet away, he could feel the heat radiating off the dark grey plastic and metal. Yes, a few feet was quite close enough. The heat would be too much to put an ear up close — and who knows what the beastly fellow inside would throw out this time.

“You there, then?” The Voice asked.

“Yes,” Martin replied.

“Excelente.” The Voice cleared its throat. “What a day, huh.”

“Indeed,” Martin said. “Scorcher.”

“You’re telling me. Scorcher. Ha! That’s right. Look, I’ll get to the point. It’s fucking boiling in here. Not much in the way of ventilation, right? The black and grey just soak up the heat and blast it right at me. Like a fucking oven, mate. I’m roasting like a stuffed turkey in here.”

“Yes, well. I imagine.”

“Doubt it. Boiling, mate. Absolutely boiling.”

“Indeed.”

“I couldn’t help overhear you telling Marjorie that you were hunting and gathering yourself a little something something to take the edge off.”

“I’m going to the corner shop, yes.”

“The corner shop! Of course. Love that place. Bossman and I have a special rapport.”

“You know the owner?”

“What? Listen, you wouldn’t mind grabbing me a little beverage, would you? I’m parched.”

“Like a San Pellegrino?”

“San Pelle— Jesus. No. No, thank you. Peroni, ideally. Stella also good. Anything similar acceptable, really. Beggars can’t be choosy. And I am begging you for a drink.”

“Beer? Really?”

“Come on, mate, be a friend. Just the one. I’m all dry and wrinkled in here.”

“Can’t you get it yourself?”

“Aren’t you going anyway? You walk right past me. Don’t be tight.”

“No, I mean — can’t you get out?”

“Fine. Don’t bother then. Christ.”

“Wait, I was only asking.”

“No, no — don’t worry about it. Go on. Off you trot. No worries. Enjoy your refreshments.” “Don’t be like that.”

“Fuck off.”

“Are you even old enough to drink alcohol?”

“Listen, arsehole. I’m not one of your towelboys. Is this how you talk to all your neighbors? Fucking hell. I didn’t believe it.”

“Didn’t believe what?”

“None of your beeswax. Piece of advice, though. Stop acting like such a prick.”

“You’re extremely rude,” Martin said, in his most authoritative voice.

“Whatever,” The Voice said. “Enjoy your refreshments. They’re best consumed alone in your own home.”

“What is that meant to mean?”

“Nothing. Off you go now.:

“Hey,” Martin said. “Hey! Hello!”

The glass deposit bin stayed silent. Martin thought about looking in through the receptacle, but the heat emanating off the black rubber was fearsome. It probably was awfully hot inside of there. And what little of the morning breeze remained certainly wasn’t making it through the deep hole that marked the only entry point in and out of the bin. At least, the only entry point that Martin knew about.

Had he handled that poorly? What if the person inside dies, Martin thought, and I’m held responsible? Would bringing a beer make me more responsible or less?

“Do you have an ID?” Martin asked. The Voice did not respond.

After a few minutes, Martin gave up and resumed his walk to the corner store.

The small bell tinkled him into the shop as usual. It was cool and dark inside the store. Martin waited a few seconds for his eyes to adjust. On the right, an open fridge section hummed. Ahead, a few aisles stood packed neatly with food. Martin nodded at the man behind the till and headed to the back, where the freezer was.

At the freezer, Martin fell into deep thought. He was looking through the glass door of the freezer, at the various lollies and ice creams inside, but he was seeing the glass deposit bin. Hearing The Voice berate him. If I got him a beer, Martin thought, could I get in trouble for supplying to a minor?

He was fairly sure it was an adult inside the glass deposit bin, though that made the method of entry and, presumably but not definitively, exit, even more mystifying. Not to mention motive. He was so rude to me, Martin thought. He doesn’t even deserve a drink.

“Made a new friend, eh?”

The comment shocked Martin out of his thoughts. He looked up at the man behind the till. The man, Aaron, was looking at him with a large grin on his face. It was a gummy smile. Untrimmed moustache hairs covered a thin top lip.

“What?” Martin managed.

“Hear you’ve made a new pal.”

“A new— who?”

“Hey, nothing wrong with making a new friend. Good on you.”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about.”

“So you haven’t made a new friend?”

“Absolutely not.”

“Who were you chatting too, then?”

“Chatting to? When?”

“Just now. Before you came in the shop. And earlier today.”

This was absolutely calamitous. Martin was frozen in place. He couldn’t formulate a response. I knew I was being watched. What was I thinking? Of course someone saw. Oh, God.

“Fine, don’t tell me,” Aaron said. “You want the usual?”

Salvation. Martin looked down at the freezer. Pulled the door aside, reached and grabbed by force of habit. Lemon and lime ice lolly. Brought it over to the till. Set it down. Fished in pocket for the coin.

“Just one?” Aaron asked. His smile was still suspiciously large for customer service.

“I always get one,” Martin said.

“Tell you what,” Aaron said. “Second one’s on me.”

“What? Why?”

Aaron shrugged. “Why not? It’s the day for it.”

Martin found the coin, put it on the counter.

“Thanks,” he said, “but one is fine.”

The bell rang him out. Sunlight blinded him. After a few minutes of pained blinking, Martin began the walk back home. As he drew near the bin, he tensed. It coughed a few times.

Martin paused.

“Are you alright?” He asked.

No response. Martin scurried home.

The ice lolly was melting faster than Martin could lick it. He would usually have grabbed sufficient napkins, or at least fought the rising tide of sticky citrus liquid, but he was agonizing over something far more serious.

Aaron knew he had spoken with the glass deposit bin. Surely, then, other people had heard the voice inside the bin. In fact, that must have been what Aaron meant when he said “friend.” And The Voice inside the bin had said that it knew the owner of the corner store. Even Martin hadn’t met him. Could it all be connected?

Martin placed the half-eaten lolly on the arm of his chair and rushed out of the front door. The sun was as strong as before. Martin’s shadow flew along the pavement as he hustled back to the store. The bell was still tinkling when he started speaking.

“So you heard it, then?”

The man behind the till started.

“Alright, Martin,” James said. “What’s that?”

“Hello James. Where’s Aaron?”

“Aaron? Gone home.”

“Why?

James cocked his head. “His shift finished.”

“Oh,” Martin said.

“What did Aaron hear, anyway?”

“Um.”

“I swear, he’s a gossip,” James said.

“Perhaps,” Martin said. “Well, perhaps you’ve heard it?”

“Heard what, mate?”

“The voice,” Martin said, slowly. “The voice coming from the glass deposit bin.”

James stared at him. His eyes narrowed a bit.

“Did Aaron tell you to say that?”

“What?”

“Is this some joke from Aaron?”

“Joke? No.”

“What did Aaron tell you?

“Nothing. Listen,” Martin said, raising his hands up, palms out. “I was going to ask Aaron if he’d heard a voice coming from the glass deposit bin.”

“A voice?”

“Yes.”

“Coming from the glass deposit bin?”

“Exactly.”

James was still staring at Martin. His face was pimply.

“No.”

“No?”

“No.”

“Alright,” Martin said. “OK.”

Oh my goodness, I’m losing it. I’m actually losing it.

“Um,” Martin said. “May I have a Peroni, please?”

James narrowed his eyes further. Looked at the fridge.

“Right,” Martin said. He walked over to the fridge and grabbed a Peroni. That’s how it was usually done.

The tinkling of the bell wished Martin goodbye before being cut off by the door closing. The heat was still fierce, though somehow more bearable with the knowledge that it probably wouldn’t get any worse at this point. The street was empty.

Martin drew up next to the glass deposit bin. Hesitated.

“Excuse me?”

Nothing

“Hello?”

Silence.

Is it finally gone?

Martin edged closer to the bin. He paused, listening intently. The pigeons were rustling around in the other bin. A crow cackled in the distance.

Was I just having heatstroke? Imagining the whole thing?

Martin tentatively reached a hand out. He formed a fist. Pulled back, prepared to knock on the bin.

Have I been talking to a glass deposit bin?

Fist touched plastic. Knock. Knock. Knock-knock. Martin hit the bin steadily louder. Soon he was pounding the bin. The pigeons flew off in fright.

“I know you’re in there!” Martin yelled. “Say something!”

His knuckles were bleeding. Martin switched to the side of his fist. Then open palm slapped the bin.

“Hello! Hello!”

Nothing. Martin’s slaps grew weaker. Then he stopped, panting, leaning against the bin. He rested his head on the top of the bin. It was still hot from the sun. His knuckles stung. The hot plastic burned. He was out of breath. His heart was still thumping, as he had been doing to the bin. The crow cackled again.

The silence of the late afternoon sunk into Martin as he lay on the hot plastic bin. Here he was, on a Sunday afternoon, doing battle with a glass deposit bin.

No chance people didn’t hear that.

He sighed. Placed both hands, one still holding the Peroni, on the bin, ready to push himself upright and resume the walk home.

“BOO!” The bin let out a loud bang.

Martin screamed. His voice broke, reformed, then swerved up into a squeal. He leapt back from the bin, staggering onto his bum. The Peroni clattered away on the pavement.

Laughter echoed out from the glass deposit bin as Martin sat, palms smarting, one hand clutched to his chest. His heart was thumping in a dangerous manner. Do I feel a sense of impending doom? Is there sharp pain shooting down my left arm?

“HAHAHAHAHA, ohhhhhhh... Hahaha, ooooooh... Oh god... Oh my god... Oh, I’m sorry mate — well, no, actually, I’m not, to be honest. You should’ve seen yourself! I didn’t know voices went that high!”

The laughter continued. Martin struggled to regain control of his breathing. The process was not helped by his mind loudly refusing to believe this was really happening. All up and down the road, thin fragments of light cut out into open air as curtains were shifted. Martin’s phone buzzed in sync with his beating heart; messages pouring into the neighbourhood chat. The whole postcode must have heard that scream. That means they can’t have missed the bangs.

But bangs could mean anything. A firework. Burst tire. Engine. Youths up to no good. The shot of a gun. The opening salvo of terror’s long-feared incursion into the beating heart of Proper England. A huge balloon.

As Martin’s internal monologue word vomited, the laughter continued, only slowing down when forced by lack of air. A cacophony of wheezes brought the symphony to an end.

“Fucking hell.”

Martin focused on breathing in a square shape.

“That was fucking priceless.”

The slices of light cut across the road and shot down the pavement. They converged on Martin. He was spotlit, sat on the concrete, chest heaving, hand on heart, tears staining his cheeks, lip quivering, Peroni bottle still slowly spinning nearby; dozens of pairs of eyes trained on him, narrowing, widening, wondering what was going on.

What was that noise? That bang? That scream?

“You should’ve seen yourself.” The Voice was audibly smiling. Wiping away his own tears, even. Martin snapped.

“WHAT!”

He scrambled to his feet.

“IS!”

Slammed his open palms on the glass deposit bin, one either side of the receptacle.

“YOUR!”

Kicked the bin repeatedly with his stronger right foot. Toes first, then side after the toes hurt. “FUCKING!”

Elbows attempting to shake the glass deposit bin, which was larger underground than over. “PROBLEM!”

Spittle flying onto the bin, shooting down into the receptacle itself. Snot slipping out of both nostrils, one strand hanging and swinging wildly.

Martin gasped. His chest burned. Palms stung. Elbows and feet ached.

“Enjoy your fucking Peroni, you rotten bastard!”

Martin pushed off the bin, swept up the Peroni — fumbling the wet glass, catching it against his chest — and tried to push it into the receptacle. As he attempted to transfer the bottle from being cradled against his chest to the bin it bounced off one of the rubber liners surrounding the hole and clattered to the floor. The sound echoed out of the hole and throughout the neighborhood. That same fucking crow cackled.

No response seemed to be forthcoming from the glass deposit bin. Martin grabbed the bottle and stormed home, pointedly ignoring the windows on either side of the road. He slammed his front door and flopped into the armchair, kicking off his slip-ons.

He was safe. His breathing slowed. Martin looked around the room, anchoring himself. What was that?

His arm felt sticky. Martin lifted it in disgust. Closed his eyes. Fucking ice lolly.

BANG.

Martin’s front door burst open. It ripped out of the door frame and clattered down the driveway. The frame itself followed soon after, pulling apart as Martin forced himself through.

Outside, Martin blinked in the harsh sunlight. He held up a massive hand to the sky. It rose above the roof of his house.

Once he had acclimatised, Martin looked down at his road. There was Marjorie, standing in his shadow. She stared at him, jaw slack, thick glasses slipped down her nose. That rat on a leash growled at him.

BANG.

Woman and dog sailed down the road. A perfect kick. They landed just out of sight — no — there they were, a little crumpled heap fifty meters away.

BANG.

Each footstep cracked the pavement and sent a thunderous vibration throughout the neighbourhood. Car alarms blared. Birds fled in panic.

Martin grasped at a crow, but it swerved his fist, leaving him with a handful of feathers. No matter.

BANG.

Martin stomped down the road, reveling in his size and strength. He crushed cars like cardboard boxes. Kicked rubbish bins down the road like pebbles.

Curtains opened and then slammed shut as he passed. In the distance, he heard a siren start up. He snickered to himself. What fools!

There was the pile of clothing and accessories that used to go by the name of Marjorie. The dog was nowhere to be seen. Good riddance.

BANG.

Martin stopped in front of the glass deposit bin. He waited. No sounds came from the bin.

The sirens in the distance multiplied. No matter. Martin felt power surging through him. He flexed his biceps, his back, his glutes and quads — Good God!

As Martin raised his right foot, his shadow stretched over the glass deposit bin. It looked so small all the way down there. What a pathetically small little object.

Martin held his foot in the air. He waited. Would the owner of the voice attempt to flee? Squirm out of the receptacle like a rat jumping ship?

Nothing happened. The sirens grew louder.

Martin slammed his foot down.

BANG!

...

BANG!

...

BANG BANG BANG! What the—

Martin sat up. He was drenched in sweat. His bedroom was dark, oppressive; the soft light of dawn sifted round the sides of his blinds.

BANG BANG BANG!

Someone was pounding on his front door. Jesus! Martin swung out of bed and rushed to the door, pulling up his pajama trousers. His unbuttoned shirt fluttered as he rushed down the stairs to the front door.

BANG BANG—

“Here! Coming!”

Martin fumbled with the latch, wincing as the bangs ripped into his tender ears. Finally, blessedly, he got the door open.

It took Martin a moment to understand what he was looking at. Blue lights flashed in his face, blinding him. Partially silhouetted in those lights were two uniformed figures.

“Morning. Martin Smith?”

“Yes?” Martin blinked repeatedly in confusion.

“Could we chat with you for a moment?”

Martin stared at the officer speaking to him. They were the smaller of the two. Only slightly smaller than Martin himself; their hat gave them an extra few inches. Their voice wasn’t high, but it also wasn’t clearly low. The uniform hid any other signs of sex. Thick toolbelt, big black boots for kicking and crushing and stomping—

“Mr Smith?”

Martin started. “Of course. Sorry.”

He led the two officers into his house. Winced at the stained armchair; hoped they didn’t notice. “Cup of tea?” He asked as they sat around his dining table.

The larger officer seemed about to agree when they were cut off by the smaller one.

“No thanks, Mr Smith. We’ll be as quick as possible so you can get on with your day.”

“Oh.” Martin wasn’t sure how to proceed from here. He stood awkwardly in the doorway. “Please,” the smaller officer said, “take a seat.”

“What’s this about?” Martin asked as he sat. “Am I in trouble?”

“No, don’t worry.”

Martin sighed in relief. The officer’s voice really was remarkably ambiguous. Just then he’d thought he’d heard a definitive dip into manhood, but perhaps it had been the scrape of the chair as he sat down. Then again, the officer certainly was authoritative. If he could only get a better look at their face, he might be able to solve this mystery.

“Mr Smith, is everything alright?”

The voice interrupted Martin’s train of thought. He struggled to force himself to focus on what the smaller officer was saying. Was the larger one just there as backup? A looming figure to intimidate him? Well, it wouldn’t work. Not on him.

“Mr Smith?”

“Ah, right. Um, yes. No. Is everything alright?”

“Yes,” the officer said. “That’s what I’m asking you.”

“Of course. Well.” Dare he? No. “Yes, quite alright. Why wouldn’t it be?”

Martin hoped that didn’t sound as defensive to the officers as it did to him. God, he wished he had made himself a cup of tea. Why were these two here, anyway? His eyes were adjusting to the dim pre dawn light. The officer’s face was clean shaven. Their lips were shapely, a little dry. Was that a shadow of a moustache on their upper lip?

The lip was moving. “—calls from concerned neighbours about you.”

“Neighbours? Me?”

“Yes, Mr Smith. That’s why we’re here. To check in with you and see if everything’s OK, and if not, to see what we can do to help.”

Martin’s heart was racing. He felt as if he couldn’t formulate thoughts properly. The damned silent oaf of an officer was looming over him from the other side of the dining table.

“Perhaps you could tell us about your day yesterday?”

“Oh. Of course. Yes.” Martin took a deep, shaky breath. What had happened yesterday?

“Well, yesterday was Sunday. On Sunday’s, I take out the rubbish. The recycling, that is.” Sweat on his back was making him itch. He wiped his upper lip. It was hard maintaining eye contact with either officer. But it was also hard not to stare at the smaller one. Was that the shape of breasts on their chest or just a fold in the coat?

“I took it out, and then— well, I suppose I had a disagreement with someone.”

“A disagreement?” The smaller officer said. “With who?”

“The glass deposit bin.”

Silence. The larger officer’s thick eyebrows furrowed.

“You had a disagreement with the glass deposit bin.”

“Look,” Martin said, desperately, “I know it sounds ridiculous. It is ridiculous. I promise I’m not joking. There is someone inside the glass deposit bin. They won’t let me put my glass inside. They insulted me. I lost my temper.”

The officers stared at him.

“Other people have heard him,” Martin added. “Ask Aaron.”

“Aaron?”

“Aaron, yes. He works at the corner shop.”

The smaller officer glanced at their partner.

“Alright, Mr Smith,” they said. “We’ll ask around about the glass deposit bin. In the meantime, though, take care of yourself. I’ll just leave you this“—they pulled a leaflet out of their pocket, placed it on the table—“for you to read.”

The leaflet was light blue. It had a large picture of a man’s face on the front. His eyes were closed and he had a faint smile. “CONTROLLING YOUR ANGER SO IT DOESN’T CONTROL YOU,” read the title.

“There’s a number on the back you can call,” the officer continued, “and a website with more advice.”

The officers stood up.

“That’s all,” the smaller one said. “Have a nice day, Mr Smith.”

Martin watched them leave. For a while after the front door closed, he sat at the table, staring into space. The room gradually grew brighter.

Eventually, Martin stood up. He needed that cup of tea. The kitchen was next door, through an archway, and was barely large enough to fit the stove, counter with sink, and fridge. Martin went through the motions. Fill the kettle. Turn it on. Grab a mug (white, lettering long since rubbed off). Open the cupboard. Select a tea bag (Yorkshire). Place bag in mug. Go to fridge. No milk. Martin looked at the fridge in disbelief. It was barren. A few jars of pickle and jam stood on the top shelf. Butter and eggs in the door. The bottle of Peroni. But no milk.

The kettle switched off. Martin sighed. Grabbed the Peroni. It was crazy, completely out of order, but so had been the last 24 hours.

Martin fished his combination corkscrew bottle opener from the kitchen drawer and opened the Peroni. He placed his palm over the top and shook it a little, then let the foam pour into the sink. Once it was flattened sufficiently, he took a long swig, then settled back into the chair. From the front hall, the clock struck five. It was almost five.

The bottle was mostly empty by the time Martin realised what that meant. It was almost five. On Monday morning. The day the rubbish truck came.

Martin leapt out of his chair, knocking the Peroni onto the carpet. He rushed into the front hallway and out of the door, not bothering to put on shoes. The morning breeze pushed open his unbuttoned pajama shirt.

Had he missed it? No, he could hear the rumbling of the truck in the distance. It was getting louder. Martin ran to the bin and leant against it, panting.

As he caught his breath, the truck appeared at the end of the road. It was a glorious sight. Orange lights flashed on each corner. At the back, large figures in neon orange uniforms hung on. The giant robot arm lay prone above the back of the truck, ready to grab and lift and crush and drop.

Martin almost clapped in excitement. He wanted to say something, but didn’t want to alert The Voice of its impending doom.

The truck rumbled down the road. It hurried for no man. Still, Martin wished it would hurry; he was bursting with tense anticipation. This nightmare was coming to an end. A bubble of a bad dream burst by this wondrous automaton and the plucky blue-collar salt of the earth fellows keeping society running.

“You can’t stand there,” a high-pitched voice said over the sound of the truck engine.

Martin looked down from the robot arm. One of the neon orange figures was walking toward him.

“Move back please.”

The woman ushered Martin away from the glass deposit bin. When he was far enough away, she turned around and gave a thumbs up. The arm jerked into motion.

Martin clapped his hands in excitement. Slowly, the arm descended above the glass deposit bin. It hovered there for a few seconds. Then, in one motion, it clamped down onto the top of the bin.

Metal ground against metal as the arm pulled the bin out of the ground. The bin just kept coming. Finally it was out; it hovered above Martin, casting a long shadow in the dawn light. He looked up at it in awe.

Then the bin was over the truck bed. The operator, inside the truck, pulled a lever, and the bottom of the bin collapsed open. The floor opened and out poured a wave of glass. The glass shattered and crashed into the truck.

A few pigeons that had braved the truck’s arrival fled from the nearby rubbish bin.

In just seconds, the bin was empty. The doors in the floor began to close.

Martin didn’t notice. It was impressive, but there had been something missing. Where was he? It? Had his tormentor hidden somewhere in the bin? Had the falling glass concealed it?

Surely no one could have held onto the inside of the bin and resisted falling out into the truck. Could they? If only he could just see inside the bin and confirm. He edged forward, ducking his head and squinting to try and look into the inside of the bin before the floor shut closed again. No good. The inside was shadowed. But surely anyone in there must have fallen out. And so much glass had been dumped that there couldn’t have been space for a man, too.

That was it. Martin was now directly under the bin. He turned to the truck and pulled himself up. The metal was surprisingly cold and slippery.

“Excuse me!”

Martin hoisted himself up, straining, trying to peek over the edge of the truck and into the bed. “Get down from there!”

He was so close. Just a little more and he’d be able to see inside. His arms quivered, fingers ached.

“Hello! What are you doing? Stop!”

The high-pitched voice was getting higher and louder. Martin ignored it, straining.

Unfortunately, Martin’s hands were less robust than the robotic arm looming above him. They gave way. Martin gasped. His weight fell onto his feet, balancing on the side of the truck. Reflexively, his arms windmilled backward. Then his body followed.

Martin’s fall was, fortunately, cushioned. Unfortunately, it was cushioned by a small figure in an orange uniform. The figure shrieked as Martin collapsed on top of her. The two sprawled on the floor with an ominous crunch.

Martin rolled to the side and tried to catch his breath. His fingers stung and his back ached from where it had hit the garbage woman.

The garbage woman began to wail. She rolled around on the floor, clutching her arm. Two figures ran up to her and started peppering her with questions. Before Martin could explain, he felt himself being hoisted to his feet.

Martin was span around. Facing him was another orange-clad figure. It looked at Martin with an unshaven, rough face. Large eyebrows were deeply furrowed.

“What the fuck is wrong with you?” the binman spat. “Fucking prick. What were you thinking?” “Listen—“ Martin said.

“No, you listen,” the binman interrupted. “You fucking idiot. You’ve broken her fucking arm. Stay here. I’m calling the police.”

“Wait,” Martin said.

“Shut the fuck up.” The binman pulled out a phone and dialed.

“Look,” Martin tried again. “There’s somebody in your truck.”

The binman looked at Martin, phone held to his ear. His eyebrows raised a little, in confusion. “There was somebody in the glass deposit bin,” Martin explained. “They fell into the truck.” “The fuck are you on about?” The binman said.

“I’m not sure how he got inside the bin,” Martin said.

The binman didn’t respond. He started speaking to somebody over the phone.

“He was extremely rude,” Martin said. “He’s probably being all cut up by the glass in the truck.” The binman walked off. Martin sighed. If he rushed, he could probably try another look inside the truck. But his fingers still ached. He massaged one hand with the other and waited.

Soon enough, the flashing orange lights of the rubbish truck were met with blue. A police car pulled up behind the truck. Two officers stepped out. One was significantly taller than the other. “Oh, fuck,” Martin muttered.

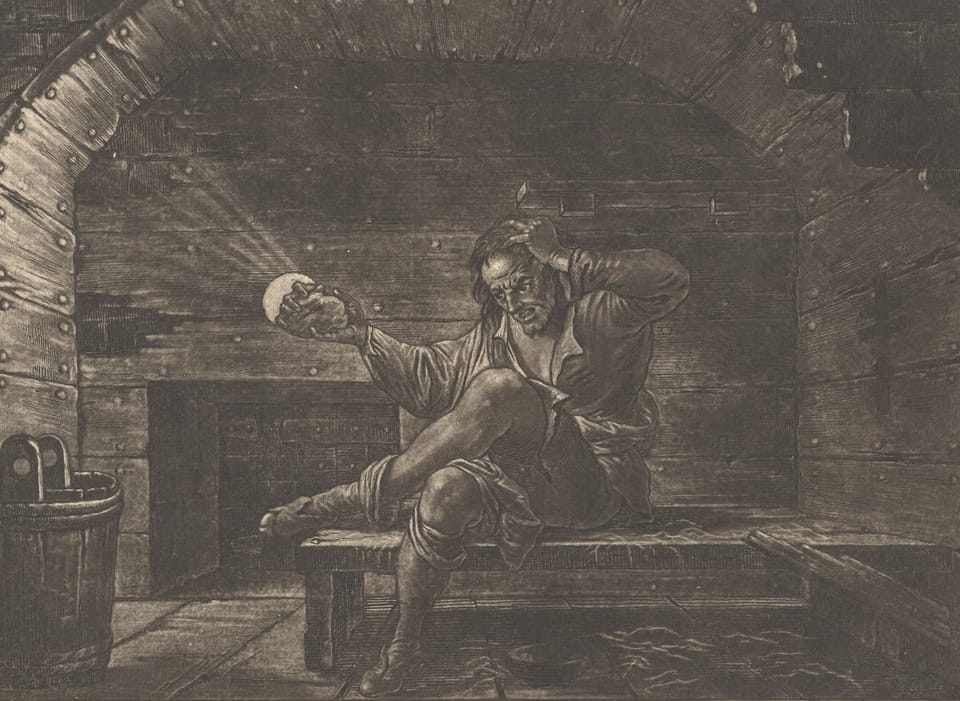

Martin looked around the interrogation room. It was dreary. The walls had once been white. His chair was unstable and uncomfortable; the metal back was dented.

One wall had a murky, translucent window embedded around eye level. The door, in the same wall, had the same window in the center. It swung open.

In walked the two officers. The tall one stepped aside and posted up in the corner. He was about as far away from Martin as one could be, but still managed to loom over him. The shorter officer sat down in front of Martin. There was a small metal desk in between them, on which the officer placed a folder of papers.

“How are you feeling, Mr Smith?”

Martin’s first attempt at a response failed. He cleared his throat. “What am I doing here?”

The officer sighed. “Listen, Mr Smith. Do you remember our chat from this morning?”

Martin nodded. Had that sigh been womanly?

“Good. Could you please take me through what happened after that?”

“Alright,” Martin said. “Well, I realised that it was Monday, which meant that the bin men were coming to collect the glass recycling.”

“Right.”

“And so I thought I should go watch them open up the glass deposit bin so I could see who’s been hiding inside.”

The officer stared at Martin. They sighed again, then opened up the folder and leafed through the pages. They were covered in typed text with some scrawled notes.

“Unfortunately,” Martin continued, “I didn’t manage to catch them. I saw the glass fall out of the bin, but didn’t see anyone fall out, though they must have been hidden by all the glass — I couldn’t quite see inside the bin to confirm, because of the light and because one of the bin men — no, it was a woman — stopped me. I tried to explain the situation to her but she refused to listen.”

The officer pulled out a biro from her pocket and tapped it against the paper.

“In fact, she started acting quite irrationally. She was shouting at me. I managed to slip past her to try and look in the truck. I’m sure the man must have fallen in, though I’m not sure how he would have avoided being cut up. But as I was trying to get up the side of the truck to look inside I fell off. Or maybe the girl pulled me off, I don’t remember. I was lucky not to hit my head

on the floor. Then one of the bin men went absolutely mad. He practically assaulted me, was screaming at me — that’s roughly when you arrived.”

“And here we are,” the officer said.

“Indeed,” Martin said. “Is that an official statement? Did you check the truck?”

“The truck is fine,” the officer replied. “Now, Mr Smith—“

“Fine?” Martin said, his voice growing louder. “Fine? Who cares if the truck is fine? It’s a damn truck! Did you find the man hiding inside the truck, is what I’m asking.”

“Mr Smith, please—“

“It’s a simple yes or no question,” Martin said in a firm, authoritative voice. “Yes or no — did you catch the man.”

“Don’t talk to my colleague like that,” the large officer yelled from the corner. His voice was a booming bass that shook the room. Martin flinched back.

“Alright,” the smaller officer said, putting the pen down. “Mr Smith, let me explain your situation. When you fell off the truck — which you shouldn’t have been climbing — you landed on the woman — not girl, woman — and seriously injured her. Mistake or not, she is in the hospital right now. She could press charges.”

“If she had simply let me look in the truck this never would have happened.”

“Mr Smith, people aren’t allowed to just look inside a rubbish truck. It’s dangerous. You tried, and the result was a serious injury. Do you understand that?”

“Yes, yes. And I almost cracked my head open. What about the bin man who attacked me? Was he arrested? Did he see anyone inside the truck?”

“Mr Smith, you were not attacked. No one was inside the truck. No one was inside the glass deposit bin.”

“You don’t understand,” Martin said, his voice rising again. “Why won’t anyone listen to me — there’s a fucking man inside the glass deposit bin and he’s making my life hell!”

“Dont shout,” the larger officer warned.

“I’m not shouting,” Martin shouted. “You aren’t listening to me.”

“We hear you,” the smaller officer said. “Have you been stressed lately?”

“Stressed?” Martin laughed. “Stressed? There’s a fucking little fellow in my bin who won’t let me deposit my glass. He mocks me. He shops at Waitrose, for God’s sake!”

“Right,” the officer said. “Mr Smith, do you have any medical history in your family?”

“What are you implying?”

“I have to ask this question, Mr Smith. Its policy. Any history of mental illness?”

“Mental— mental illness? Me? Are you fucking kidding me?” Martin shrieked. “I won’t sit here and be called insane by some androgynous midget in a hand me down officer costume!”

“That’s it,” the larger officer said. He stomped over and hoisted Martin up out of the seat. “Unhand me!” Martin yelled.

“Shut up,” the officer said. Martin struggled, but the man’s hands were like iron. He dragged Martin out of the room and practically carried him down the hall. In the foyer, the officer shook his head at the receptionist, who buzzed open the front door.

“Help!” Martin cried. “Help me!”

“Crazy old prick,” the receptionist muttered.

The big officer dragged Martin out of the door and pushed him onto the street. Martin stumbled, his shirt flapping in the wind.

“You’ll get a court summons in the mail,” the officer said. “See you there.”

The door slammed shut. Martin blinked in the morning sunlight. His heart was racing and his wrists ached. People were on the street, looking at him. He started buttoning up his shirt. A bus rounded the corner and pulled up outside the station.

Martin slumped into his chair and groaned. His wrist still ached. It was stuck to the sticky patch on the chair handle. He peeled it off and pulled off the top of another bottle of Peroni he had picked up on the way home. It was covered in condensation.

He took a deep drink, swallowing until the bubbles made him hiccup.

No mail came that day.

By Saturday, the cupboard under the sink was full of glass. Martin stuffed a jam jar inside, cursing for the hundredth time the loss of his cardboard box.

There was a thunk from the front door. The letterbox!

Martin hustled through the house. Under the letterbox, on top of a pile of flyers and junk mail, was a thick, official-looking envelope. On the front was an ornate, royal logo. The letter was from HM Royal Courts.

Martins hands were trembling as he picked up the letter and ripped it open. Inside was a single folded piece of paper. Martin read it. Then read it again. It wasn’t a court summons. In fact, it wasn’t summoning Martin anywhere. Quite the opposite. The letter was a restraining order. Martin was henceforth officially banned from coming within 50 feet of the glass deposit bin. Punishment was a fine. Further offences could mean prison.

Martin stared at the letter for a long while. Eventually, he felt it slip out of his hands. This didn’t make any sense. Where was he meant to put his recycling? The other bin? Where was that? He threw open the front door, pushing aside the pile of mail, and stomped down the front steps. Instead of turning left, he went right.

Down the road, Marjorie and her dog were approaching. Upon seeing him, she crossed the road. Martin pressed on. Left. Right. Right again. The familiar neighbourhood shifted gradually. Recognition faded.

After miles of walking, Martin arrived at the next-nearest glass deposit bin. Sweat ran down his face. His shirt was soaked.

There was a young man standing in front of the bin. He was putting bottles into the bin. Martin flinched each time, but nothing strange happened. The bottles went into the bin and clattered inside. None were thrown back out. No voice called out in anger or mockery.

The man put the last bottle in the bin, wiped his hands on his trousers, picked up his now empty bag, and walked off.

Martin edged toward the bin. He circled around it once. Twice. Knocked on one side, then the other.

“Hello?” Martin said. He put his mouth up against the receptacle. “Hello?”

Silence.

“Listen,” Martin said, “if you’re there. I don’t know what to do. I can’t bring all my glass here. I want to use my own glass bin. It’s so unfair. No one believes me. If I could just get a look inside the bin...”

Martin paused. That was it.

“You alright mate?”

Martin leaped back. Span around. The young man raised one hand placatingly.

“What are you doing?” Martin said.

The man lifted the bag in his other hand. It was full of glass again.

“Using the bin, mate. That OK?”

“Oh,” Martin said. He straightened up and cleared his throat. “Right. Yes. Sorry.”

Martin sped walked away. At the corner, he turned around and looked back at the bin. The man was using it again. All proceeded as normal. After a few minutes, the man looked up and over at Martin. He smiled.

Martin fled.

Martin pushed open the front door, straining as it swept aside growing the pile of mail in the front hallway. He closed it with one hand, the other dragging a packed shopping bag.

The front hallway was lined with glass bottles and jars. In the kitchen, Martin pushed aside the glass crowding the table and heaved the shopping bag up. After pulling out empty bottles from the fridge, he replaced them with new, full bottles — of wine, beer, cider. One of organic ketchup. A small jar of marmalade. Martin left one six pack of Corona in the bag. He pulled one out, pulled off the top, and drank half of it, warm.

Holding the bottle in one hand, Martin walked back to the front door. He checked it was shut. The pile of mail was all junk. With one foot he sifted through it to be sure. Nothing else important had arrived since the restraining order. That had been days ago— weeks? Months?

The glass situation was becoming untenable. At first, Martin had stuffed empty bottles into the cupboard under the sink. When that was full, he placed empties on the kitchen counters. Then other surfaces. Soon glass lined the halls, crowded corners, and narrowed the available space on the stairs.

Martin hadn’t dared try the glass deposit bin. On Monday mornings, he spied the truck from afar, squinting through a cheap pair of binoculars. After a while, he saw a small orange-clad figure with one arm in a sling. Other than that, nothing unusual.

He had occasionally tried to bring up the subject with neighbours. Marjorie refused to be near him. The rest were polite but aloof.

In all honesty, it was sickening. These were people he’d lived with for years — decades — and they tossed him aside like an empty bottle. He was drained, empty; waiting to be taken away. Martin spent most of his time in the house. He got food delivered. Sometimes he risked a journey to the second-closest shop. The route did not take him anywhere near the glass deposit bin.

In the evenings, Martin researched on the computer. He spent hours trawling forums and struggling to understand patents. Nothing indicated that the model of glass deposit bin — any

bin, actually — could permit the entry and accommodation of a grown man. Even a child, really. And the volume of glass that poured out into the truck often implied that the bin was full.

The fundamental question, though, which plagued Martin, was how everyone had managed to get in the know about the bin, when he hadn’t. Now, of course, he knew the truth, or knew there was a truth, but it was too late. He’d already exposed himself. But when had Aaron, Marjorie, and the others figured it out? When had they been told, taught, about the bin? Why hadn’t Martin?

These were the questions Martin turned over day after day. He was unable to reach a satisfying conclusion. All the while, as he tried to figure it out, the glass piled up.

Martin was woken by a thump. He started, wiped drool off his chin. His arm had stuck, again, to the armchair, in which he had dozed off.

He struggled to get out of the chair and followed the path in the glass out of the living room, through the hallway, and toward the front door. The clock read 6:33. Martin was unsure what that meant. The top of the clock was full of glasses.

The pile of mail looked the same. Martin stared at the letterbox, uncomprehending.

Then it jiggled. The metal flap opened inward. A glass bottle pushed through and fell to the floor, its landing muffled by the pile of paper. The letterbox slammed shut with a thunk. The bottle slid down the pile and came to rest among the rest of the glass lining the hallway.

Martin stood among the glass and watched as bottle after bottle was pushed through his letterbox. Soon, the bottles weren’t sliding all the way off the mail. Subsequent bottles clattered against the glass in loud cracks. One broke in half.

After some time, the bottles stopped coming. Martin gave it five minutes. When he was sure none more would come, he stepped up to the front door and pulled it open. The door was heavy, pushing aside the paper and glass in the hall.

There was no one outside. Shadows flitted across the lawn and street in the gloaming. The streetlight off to the left flickered. A bird on top, silhouetted, cackled.

Martin shut the door. He pushed aside the new glass with his feet, renewing the clear corridor. Then he walked along the piles of glass back to the armchair.

Want to see which stories this connects to? Subscribe for access to all content. It's free.

Member discussion