Oblatio

Climb up on the pillar and leave the world below. And if the world climbs up to join you, what will you do? Chapter 5. Rohan Montgomery.

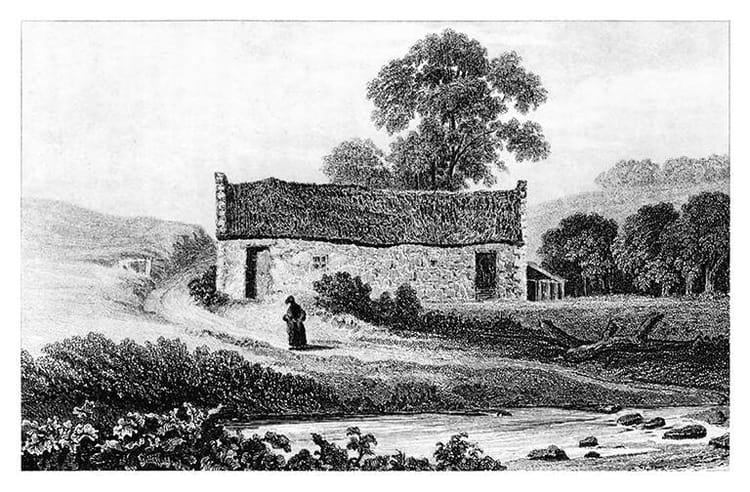

Dareste surveyed his kingdom and was unimpressed. God’s kingdom, that is, stretched out before him, dusty and barren. He looked down at it from atop the stone pillar he’d built over the last year.

God’s kingdom. Less than a mile to the east, the city walls, as tall as the pillar but unmanned. To the north and south, arid scrubland stretching into hills and then, finally, mountains. A road led from the city entrance, past Dareste’s pillar, and off to the west, to the rest of the world.

Even here, so close to the city, the road was little more than a well-trodden track. The Empire’s stones had long since been pillaged, repurposed. Dareste had used some himself to construct his pillar. He had kept any inscriptions pointed inward, in case legionnaires or officials came from Constantinople, though that hadn’t happened in many years.

Dareste’s pillar. God’s kingdom. God looked down at his kingdom and was unimpressed. How many generations had it been since the truth was revealed? And yet here Dareste was, watching countless travelers walk past in darkness. How many lives had been sacrificed to spread the word? And yet the city refused to listen.

God could only take so much.

Everyone who entered and left the city had to pass along this road, and now that road led them directly past Dareste’s pillar. He stared down at passers-by. He sat in quiet reflection.

He ate food brought to him by his mother. She brought it in a bucket which Dareste pulled up by rope. Waste was disposed of in the same manner.

That first week had been euphoric. On clear days, when the sun was high and the air thinner than usual, Dareste could look westward, along the road, over the desert and the sea, and almost see Constantinople. He pictured it in his mind. Clean, orderly. Church bells, crowded masses. Glorious monuments proclaiming everlasting faith to last until the end of time. However long that was.

Faint clouds of dust warned Dareste of a caravan’s arrival long before it arrived. He assumed a judicious position and waited. Let these pagans witness the power of faith!

The dust materialized into a single man on horseback. Dareste resisted the urge to slump, forced his back to remain straight. The man slowed his horse before the pillar.

“Hello,” the man said.

“I have confined myself to this pillar,” Dareste proclaimed, “to inspire those who live in shadow to see the light!”

The man scratched his beard and looked at the city. The walls and red tiled roofs behind glowed in the sunset.

“The light of God,” Dareste specified.

“Oh,” the man said. “Which one?”

“The only one!” Dareste said. “The one who sent his Son down to Earth to die for our sins.”

“Ah,” the man said. “I see. And you built that pillar, did you?”

“Yes,” Dareste said.

“Huh,” the man said, looking the pillar up and down. “Nice work. You know, when I first saw you up there, I took you for one of those cultists obsessed with the sun. Or with destroying it. I can never remember whether they love it or hate it. But that’s some nice stacking there. Must have taken you a while. No crazy person is patient enough to do all that stacking, I know that much. Me, I prefer to stack smaller things. Boxes, cups—”

“What do you mean, cultist?” Dareste said. “Of course I love God’s Son. He sacrificed himself to save us all!”

“Right, right,” the man said. His horse snorted, eager to reach the end of their journey. “Well,” the man continued. “As long as you’re not part of the city watch.” He chuckled.

“God sees all!” Dareste reminded him.

“Sure,” the man said. But he’d already spurred his horse into a leisurely walk. The pair followed the road into the city.

This was more or less how every conversation went. At first, Dareste was angered. But he came to realize that this first man had not been rude. Actually, he was one of the polite ones.

Most travelers who engaged Dareste in conversation used far… cruder language. They apparently delighted in watching Dareste squirm in discomfort or shake his fists in impotent anger. After all, what was Dareste going to do? He was stuck up on top of his pillar.

Near the end of the first month, urchins from the city decided Dareste was in the same category as a sickly stray dog. They tormented him without fear. At first it was miming lascivious acts and making inappropriate noises, which made Dareste blush. When he learned to ignore this, the children began throwing pebbles at him. Then clumps of dried dung. Dareste dodged. He warned them of God’s wrath.

Only the appearance of Dareste’s mother drove the urchins away.

That, or a traveller. So it was in the third month when Dareste, exhausted and demoralized, had two strange encounters on the same day.

In the morning, he spotted a large caravan approaching the city. As it grew closer, Dareste stood and squinted. The figure on the lead horse was dressed in vestments. They were dusty and a little ragged, but still clearly marked him as a clergyman. That was more than could be said for any of the so-called religious leaders in the city.

As the priest and his retinue drew closer, Dareste became nervous. This would be the first time a true Christian had passed his pillar.

The priest stopped next to Dareste and looked up. Darested made the sign of the cross. The priest sighed, shook his head, and set off again.

“Father!” Dareste called. “What brings you to the city? Have you been sent to drive out the disbelievers?”

The priest turned and regarded Dareste with watery blue eyes. His cheeks were red and flaking. He cleared his throat.

“You know,” the priest said, “you make us look bad.”

Dareste stared, mouth open.

“Christians,” the priest clarified. “You give us a bad name.”

He spurred his horse into faster motion. Dareste watched in disbelief as the priest and his party filed into the city. He couldn’t understand what he’d heard. Was the priest a foreigner? His accent had been strange. But he’d spoken clearly enough.

Before Dareste could sort through his thoughts, a voice came from beneath the pillar.

“Excuse me?”

Dareste jumped. “Who’s there?” He said.

“Down here,” the voice said. Dareste peered over the edge of his platform. At the base of the pillar, huddled in its shadow, was a young man. He wore little more than rags and his hair and beard were dusty and matted.

“What do you want?” Dareste snapped.

“Peace, peace,” the man said. “Solely to know why you are up on this pillar.”

“Ah,” Dareste said. “Yes. I took a vow to confine myself to this pillar. I rejected, and continue to reject, the sinful trappings of the modern world, so that those who pass and who live in shadow might be brought into the light. Of God,” he clarified.

“Of God,” the man repeated. He looked toward the city. A few birds circled lazily overhead in the afternoon sun. “Is it as bad here as you say?” The man asked.

“Worse,” Dareste said grimly.

“And many people pass by you each day?”

“Indeed,” Dareste said, puffing out his chest somewhat.

The man absorbed this.

“What of your homeland?” Dareste asked. “Or the lands through which you have travelled?”

“Who built this pillar?” The man asked.

Dareste blinked. “Well,” he said, “I did.”

“You!” The man exclaimed. “And you were permitted?”

“Why would it be otherwise?” Dareste asked.

“Wow,” the man said. “Worse indeed. Nevermind.”

“What is your name?” Dareste asked.

“Samat,” the man said.

“Hail, Samat. Have you heard the good news, then?”

“Which news?”

“That our Lord God sent his son to die for our sins.”

“Oh,” the man said. “That news. Sure.”

“Excellent,” Dareste said.

Samat nodded and continued along the road to the city.

Dareste’s mother was unusually agitated when she arrived that evening. In fact, she almost upturned the waste bucket while taking it down.

“Mother!” Dareste said. “What is it?”

“Nothing,” she said.

“Should I pray more for you?” Dareste asked, worried.

“No, no,” Mother said. “Listen, Dareste… how much longer are you planning on being up there?”

“I made a vow!” Dareste said. “I cannot break it!”

“Of course not,” Mother said. “It’s just…”

“Don’t worry about me,” Dareste said. “I am fine. I feel closer to God than I ever have.”

Dareste’s mother sighed and attached the food bucket to the rope.

“Did you see the priest?” She asked.

“Indeed,” Dareste said.

Mother groaned.

“What”? Dareste asked. “What is it now?”

“He is… unhappy that you’re here,” Mother said.

Dareste nodded. That had seemed to be the case. However, people often reacted badly to new ideas. Even the most holy — well, Dareste might be faithful, but he wasn’t foolish. It had been many years since anyone was martyred, but still. The thought had occurred to him. It made him shiver with excitement.

Mother sighed again and set off back to the city. Dateste resolved to say additional prayers for her peace of mind tomorrow morning.

He was interrupted by the sound of footsteps. The sky was still pink, and the air hadn’t quite lost the coolness of night. Dareste saw a lone figure walking out from the city. He remained seated and waited.

Every so often, one or two people left the city to speak to him. Or just look at him. They were more curious than anything else. None came twice.

“Morning,” Samat said.

“Blessings on you,” Dareste replied.

“So,” the man — Samat — said. “You really do stay out here all day.”

“And night,” Darested said.

“Sure, sure,” Samat said. But you must leave to eat.

“No.”

“Don’t tell me God provides.”

“My mother brings me food and water and disposes of my waste.”

“How dedicated of her.”

“She assists me because my task is righteous.”

“Is it?”

“Well, yes.” Dareste hesitated. None had challenged him at this. “Those entering or leaving the city must pass my pillar,” he said. “They will be forced to acknowledge that their Lord and Savior awaits their souls.”

“That’s a little arrogant.”

“What? No — you misunderstand.” Dareste flushed. “I am, of course, not the Lord, but merely a reminder of that Lord. And of the eternal damnation that awaits them, should they remain in sin.”

“So you’re only their savior then.”

Dareste narrowed his eyes at Samat. “Do you mock me?” He asked.

Samat laughed. “No, no,” he said, raising his hands in protest. His fingernails were ragged and filthy.

“Are you a Christian?” Dareste asked.

“Sure,” Samat said. He crossed himself with his left hand, then clasped his hands and bowed. “Forgive me, holy one,” he said.

“Stop that!” Dareste shouted. “Don’t call me that.”

“Apologies…, oh holy one.”

Dareste took a deep breath. This was, he determined, part of the test. Really, should he be surprised? Was it not through whispering that the serpent drove Eve out of paradise?

“So,” Samat said. “How much does the church pay you to stay up there, saving all these poor souls?”

“Pay? Why would they pay me?”

“Good question,” Samat said, smirking. “Then you must receive donations. Gifts, sacrifices. From worshippers.”

“Your mockery has no effect on me,” Dareste said. “I will pray for your soul.”

“Oh, thank you, oh holy one!” Samat said. He remained for a while, watching Dareste, the road, the city. The sun rose and the air grew hot. No breeze offered relief. Samat squatted in the shade of the pillar. Dareste sat on top of the platform, sweating under his wrap. The soul prospers, he thought, as the body weakens. It is by warfare that the soul progresses.

Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner.

Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner.

Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner.

Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy—

A telltale dust cloud on the horizon to the west. A caravan. Dareste stood in anticipation, subtly stretching his aching legs. The travelers were likely hours away yet. They would barely make it to the city before sundown.

This close to the walls, it was generally safe at night, but still. Dareste remembered hearing stories as a child, from his uncle, of when the Empire had stretched beyond the city, and a traveler could lie down at the side of the road and awake to continue his journey unmolested. That was just a few generations ago. These were strange times.

The caravan was a large one. Two dozen animals and many more people, most on foot. Dareste crossed himself. The travellers were dark figures silhouetted in the setting sun. Their faces materialized as they approached the pillar. Each looked haggard and drawn. Some of the men had bandages wrapped around their arms, chests. None had one on a leg.

It was only then, as the beleaguered group approached the pillar, that Samat rose. He stepped out onto the road, standing between the group and the city.

The caravan slowed, halted. At the front was a magnificent horse. It was deep brown and tossed its head in annoyance at the interruption. On it sat a straight-backed man dressed in a linen tunic and coat of mail. His head was covered in a linen wrap and his mouth framed by a neat salt and pepper beard.

The man guided his mount forward and looked down at Samat.

“Welcome!” Samat said, holding his arms open wide. “Welcome, weary travelers! God has blessed you, brought you here safely.”

The man remained still, regarding Samat. He looked up at Dareste, who made the sign of the cross and bowed.

“Are you a man of the desert?” The rider said to Dareste. His voice was gravelly, parched.

“We are all men of the desert here,” Samat said. “God placed us here to welcome those such as yourself—”

The rider shook his head.

“Are you a disbeliever?” Samat asked. “A heathen? Do you deny the words of our lordship?”

“Do you see all who enter?” The rider asked Dareste.

“Indeed,” Samat said. “All who pass are blessed by the Son of the Desert Father.”

“Have you news from the south?”

“Of course, my dear traveler,” Samat said.

“Tell me,” the rider demanded, finally looking back down at Samat. Dareste felt relieved to have that gaze off him. He’d been frozen under it. And confused at what exactly Samat was doing.

“I would be glad to share my news with you,” Samat said. “But first, observe the holy desert man keeping watch over this road, this city, in the heat, whose prayer brought you here safely through dangerous, barbaric lands, past marauding—”

“Why are you up there?” The rider asked Dareste, looking back up at him. Those eyes, almost black, unblinking, lined with deep wrinkles that seemed to accentuate the iron gaze. There was a surety in them, in the way the rider held himself, spoke. Dareste struggled to find words.

“Good sir,” Samat said, “it is as I spoke. The holy man of this desert prays over—”

“What do you want?” The man demanded of Samat.

“Merely a small tithe,” Sama said, bowing, “so that our holy father might acquire some sustenance and a drop of water—”

The rider reached into his linens and pulled out a small leather pouch. Before Dareste could protest, the rider pulled out a small chit and tossed it toward the pillar. It sent up a puff of dust.

Samat hustled off the road and plucked the coin from the ground. He tucked it into his sleeve and bowed toward the man.

“So,” the rider said. “What news?”

“Aha,” Samat said, “news. From the south. Yes, we receive the occasional traveler from the south. Odd men, exotic women. Dark skins, like clay, with bands of gold. After a drink or two they share secrets from their far off lands.”

He stopped. The rider waited. Someone in the caravan coughed.

“Good sir,” Dareste said. His voice broke. He cleared his throat. “Sir, please forgive this poor sinner. I do not know this man.”

Dareste ignored Samat’s glare. He held his gaze as the rider turned those eyes on him.

“And have you any news?” the rider asked.

“People generally do not tell the news to me,” Dareste said. His usual speeches about the Good News somehow didn’t seem appropriate. “I do not ask. If you are in need, I will pray for you, so that you find the news you seek.”

The rider considered this. Dareste held his breath. Finally, the rider nodded. “If you see anyone of Arabia, send word to me. Do so and you will be aiding the Romaioi.”

Dareste nodded. The Romaioi? He hadn’t heard this term before. It sounded like Romans. Christians!.

The rider looked down and raised his eyebrows in surprise. Samat had disappeared. No, Dareste realized, he had slunk to the other side of the pillar, hiding from the rider.

Dareste motioned downward with his head. The rider narrowed his eyes.

“I,” he intoned. “Who am I?”

Dareste’s mouth dropped open. Obviously he didn’t know who the rider was. But those words… They were the beginning of a phrase Dareste had read time and time again. Slowly, painfully, over and over. He’d learned to read those words.

The rider noticed Dareste’s shock and nodded. “I saw you as a true follower of the Desert Fathers,” the rider said. “Better you stay silent.”

“So that evil be not increased,” Dareste finished the phrase.

The rider nodded. “Keep watch, follower of Simeon,” he said.

Dareste bowed. How was this man, clearly battle-hardened, aware of holy men, of obscure traditions born deep in the desert? Where had he traveled, what had his eyes seen? As the rider shrank away along the road to the city, Dareste felt his world inverting. The expanse of the valley around him morphed into the view from a cell window. Around him were walls, three god-made. He paced, mentally, back and forth on his pillar.

And keep watch? The city suddenly seemed so far away. Dareste strained to hear the sounds he’d grown up with. So familiar he’d never noticed them until now, in their absence.

Perhaps his mother knew something. She’d clearly been upset. Uprest, maybe, caused by some incident. Surely nothing as bad as famine, or mother would have said something.

Dareste started. Where had Samat gone? He wasn’t under the pillar anymore, nor nearby. Must have slunk off while Dareste was lost in thought. Foolish, Dareste chided himself.

The sun sank. Nobody left the city. No travelers approached from the west.

Dareste found it difficult to focus on his prayer.

Mother never came.

“Dareste! Dareste! Wake up!”

Dareste snapped awake. He blinked, confused. It was still dark. The moon had long set, and the sky had only just started lightening.

It took Dareste a moment to perceive the figure hissing his name. Under the pillar stood Mother. She had one arm stretched up, reaching halfway up the pillar, as if to shake Dareste awake.

“Mother?” Dareste said. “Why are you here now?”

“Dareste! You’re awake, finally,” mother said.

“What’s the matter?”

“Listen, son. You must come off that pillar now.”

“What?” Dareste groaned inwardly. This argument again?

“I’m serious,” mother said. “You’re in danger.”

“No more danger than I was—”

“Quiet, Dareste. Listen to me. People are talking about you. They’re asking me questions. There are rumors. I even overheard someone at church claiming there was an army coming to the city.”

“Nonsense.”

“You don’t know that. We haven’t heard from anywhere to the south in months. And before that, more travellers, more foreigners, and many speaking of war.”

“Far off. Fanciful tales.”

“You don’t know that. You’re always so sure of yourself. What if you’re calling the wrong kind of attention to us?”

Dareste blinked. “What? How am I calling attention to you?”

“It’s not natural! People don’t live on a pillar out away from their family, from anyone.”

“We’ve discussed this, mother. That’s the whole point. I took a vow to renounce—”

“I don’t care about your silly vow! What about your duty to your family? Don’t tell me that’s not important. We didn’t have you instructed to read for—”

“Of course it’s important,” Dareste said, feeling his voice grow louder but unable to stop it. “But my vow—”

“Dareste, don’t shout. Don’t you dare shout at me now. I’m your mother. Listen to me. People are unhappy with you being here. They don’t like it. The priest doesn’t like it. I don’t like it.”

“You don’t have to like it,” Dareste hissed.

“I don’t, do I? Fine. Do it yourself, then.”

Dareste watched, stomach churning, as his mother stormed away from him. She faded into the darkness, her footsteps echoing around the valley for a little longer before dissipating too. The food bucket sat in the dust at the bottom of the pillar, empty.

Dareste’s anger subsided not long after. What was happening? He was utterly disoriented. A weight settled in his stomach as he heard his mother’s scolding over and over again. They’d squabbled before, often even, but rarely like this. The last time, actually, had been when Dareste set out to start building the pillar.

Dareste’s stomach growled. But he knew it would be thirst that forced him from the pillar first. His mouth was dry from sleeping, and he hadn’t drank since last morning. Making it through the day would be tough, and without help he’d have to go back the next morning if he wanted to avoid dying on his pillar — or while attempting to make it home.

Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner.

Dareste adjusted himself, straightened his back, and resolved to last out the day at least. As the sun rose, he pulled his wrap over his head and closed his eyes, chanting silently.

The sound of distant footsteps broke through Dareste’s internal monologue. He opened his eyes and immediately squinted in pain. The sun was bright, even through the hood of his wrap. Too bright to see where the noise was coming from.

Eventually, Dareste made out a group of figures heading out of the city. They shimmered in the sunlight. He couldn’t tell how many people there were.

The shapes became clearer as they neared. A large crowd of people, it seemed. Some in the center were carrying some kind of wooden object, much larger than any one of them. Dareste remembered his mother’s words. He’d been waiting for something like this, at least in the back of his mind. Now that it might be here, he felt completely unprepared. The mob grew closer. They weren’t saying anything. The only sound was the drumming and scuffing of dozens of feet on the dusty road.

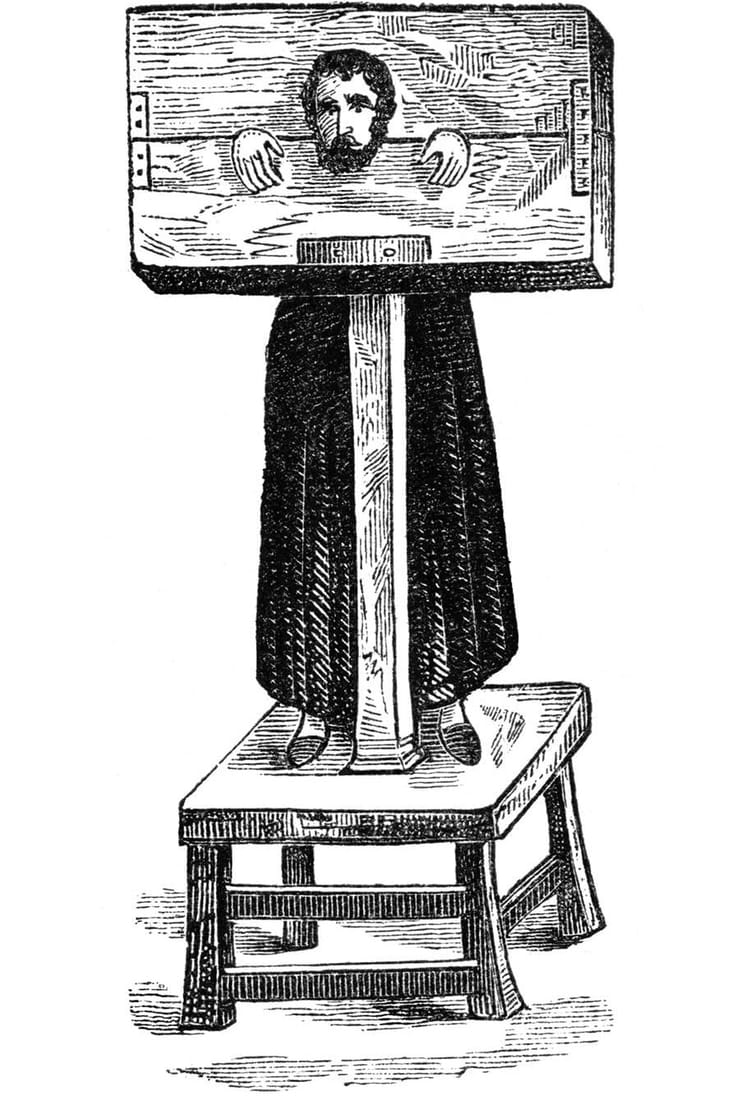

Dareste remained sat as his visitors arrived. Perhaps a hundred people, maybe two hundred, gathered around his pillar, staring up at him. Off to the side, a group set down that large wooden object. A collection of long wooden planks lashed together in a sort of narrow, very long barrel.

Near that group stood a familiar figure. Even among this relatively rough crowd, his ragged beard stood out.

“Samat,” Dareste said, his voice hoarse and weak.

“Dareste!” Samat called. “I’m touched you recognize me, my friend.”

“What do you want?”

“Ah, but your throat sounds so dry,” Samat said. “Please, allow me to offer you a drink.”

Dareste tilted his head. He hadn’t expected that. Well, as suspicious as he was of Samat, he was parched. His throat ached from the few words he’d forced out.

He nodded.

Samat gestured and a man near him pulled a waterskin from under his cloak. The man walked over to the pillar. Dareste reached out. The man placed the skin by the base of the pillar, on the ground. It wasn’t even in the shade.

Dareste stared at the waterskin. He felt his face redden, hopefully unnoticeable in the sunlight and under his hood. Of course Samat wasn’t here to help him. Of course his last day would be one of humiliation.

“Come on,” Samat said. “What harm is there in grabbing a drink? You’re letting the sin of pride rule you.”

Dareste wanted to shout back. You know nothing of sin! He thought. No — Samat knew too much about sin. But these people with him, how had they been conned? Dareste strained to make out their faces. Many wore wraps, and the light washed everything out.

“Well,” Samat said, “we’ll just leave that there for you. Plenty more where it came from.”

Samat turned and spoke to the men around him. They positioned themselves around the long barrel, five on each side and four gathered around one end. Samat barked an order and the group of four heaved the end up. The men strained to lift the barrel, tipping it slowly, carefully, until it stood upright.

The barrel wasn’t a barrel at all. It was a pillar. The wooden pillar stood on the opposite side of the road to Dareste.

He watched in horror as another group of men hoisted Samat up and onto the wooden pillar. Now it was upright, Dareste saw the base was a little wider than the top. One of the men passed up a cushion, which Samat placed under him. Another threw up a bundle of sticks and cloth, which Samat set about setting up into a sunshade.

Soon, the wooden pillar had a little pavilion on top. Samat sat inside, looking out at Dareste. The wooden pillar was slightly taller than Dareste’s, so Samat was looking down. He pulled a waterskin out and took a deep drink, smiling.

“Dareste!” Samat called. “Feel free to take a break. I can handle things here. Or, I should say, from up here.” He snickered.

Dareste couldn’t speak. His throat was closed up, not that he knew what to say. Samat was crazy. Or had a devil whispering in his ear. The afternoon sun was relentless, and even the short distance across the road was enough for Samat and the pillar to warp and shimmer. It was all a mirage.

No, the crowd was very real. Dareste could smell them. Could apparitions smell? Some headed back to the city immediately, but most hung around, as if waiting for something.

That thing came soon enough. Samat spotted the dust cloud first, calling down to the crowd. Those who’d sat stood up. Expectant whispers rushed around.

The dust gradually materialized into a family trudging along the road. The man led a tired donkey, laden with several sacks. Behind him walked his wife and a handful of increasingly small children. Their clothes were dusty.

The group slowed before the two pillars, the children gathering behind the woman, who waited by the donkey as the man stepped forward, making the sign of the cross.

“Welcome, fellow Christians!” Samat called. “Be not afraid! You are in enlightened lands.”

The man smiled, made the sign of the cross again.

“Your faith has guided you to safety, my friend,” Samat said. “I foresaw your arrival and prayed for you, as did my followers. We are glad to welcome you, and your family, to our humble city.”

The man’s smile shrank a little. He bowed.

“It is evident you have travelled far,” Samat continued, oblivious. “You are likely hungry, thirsty. Please, rest a moment. Have a drink.”

At that, one of the people under the wooden pillar stepped out, waterskin in hand. The man flinched back, his smile disappearing. His hand went to his side before relaxing as he realized the person approaching him really was offering water.

The man took the skin and passed it straight to his wife. She took a mouthful before holding it for each of her children. When they were done, the man took a deep draught, then handed the skin back to the person who’d given it to him.

“Excellent,” Samat said. “Now, please, let us pray!” He put his hands together and watched as the crowd underneath bowed their heads. The man watched, then copied. His eyes stayed open.

“Our father,” Samat began. “In heaven. We thank thou for answering our prayer. Thank thou for bringing this family here safely. Blessed are those who follow thou will. I bless this family in thou name. I bless thou who brought them here safely. May thou power protect them, and us, and thou city. I bless thou all in the name of Jesus Christ. Amen. Amen. Amen.”

“Amen,” the crowd murmured. The man made the sign of the cross again, his head bowed.

Samat whispered something to a lanky figure directly underneath him, who picked up a small wooden box from the floor and began walking through the crowd. People put chits inside. Dareste heard the small coins ring as they were placed in the box.

The lanky man left the crowd and held the box up before the man and his family. The man stared at the box, then at Samat, realiszation dawning. He reached into his cloak and pulled out a small coin. It went into the box.

No one moved. The man’s face darkened. He pulled out another coin. Placed it in the box. Dareste heard the clink.

The lanky man shook the box. More? Dareste held his breath. Should he say something? His throat burned. The man looked back at his family, then at the crowd gathered between the pillars. When had they moved onto the road like that? Some held what looked like spare planks of wood from Samat’s pillar.

The man cursed under his breath in a language Dareste didn’t recognize. He reached into a different part of his cloak and pulled out a small leather wallet. With an angry tug, the man pulled open the bag and emptied its contents into the wooden box. Whatever fell out sounded heavier than the chits, if only a little.

“Your generosity will not go unnoticed, brother,” Samat called. Dareste relaxed. The crowd parted ways, and the family filed through, both adults glaring, the children huddled together. Dareste watched them pass.

The woman met his eyes and Dareste was struck with the hatred in her stare. He felt slapped. His heart thumped in his chest. With horror, he looked around and realized he was just another part of the mob to this woman.

Dareste watched helplessly as successive groups of travelers fell victim to the performance. Some gave more than others. Samat seemed to have a sixth sense for when he’d pushed a person to the limit. Right as Dareste was sure they’d refuse to give any more, that the crowd would break out into violence, Samat would call out, breaking the tension. Sometimes he made up a prayer. Other times he blasphemed outright, offering vapid blessings or false bestowals on particularly generous — or compliant — travellers.

Each time the victim would look at Dareste at least once. Each time their eyes were filled with reproach, hurt, anger. Dareste knew enough to know that many were likely giving away the last they had.

Dareste felt as though he was receiving lashings. Samat and the mob flayed him with their display. On and on the day went. Dareste had never seen so many travellers pass before. Just his luck.

Eventually, Dareste just closed his eyes and waited for night to fall.

Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner.

Dareste sat on his pillar and surveyed the world before him. His kingdom. Nothing was there. His pillar stood alone in the midst of the nothing. Of nothing but darkness.

He was unimpressed.

Hadn’t we reached the first day already? What was God waiting for?

“Oh, Holy One!”

Dareste jumped. What was that? A voice, a disembodied voice. It seemed to come from above.

“Most Holy Father of the Desert!”

The voice drifted down as if from a great height. Dareste craned his head back to look up.

“Pass judgment on me, O Great Father!”

Wait. Dareste looked back down. There, in front of him, was another pillar. He could almost touch it. How had he not seen it before?

The other pillar stood amid the nothingness, next to Dareste’s pillar. But it stretched up, up, far up above, so Dareste squinted but could not see the top. It was from there that the voice came echoing down.

“I am an Angel sent to you!” the voice called. “Judge me, Father!”

Dareste’s head spun. The voice sounded familiar. It wheedled and mocked. Why was this pillar in his kingdom? It was so much taller than his pillar. Think of how much effort it must have taken to build! The dedication to complete it, to climb up and remain, the closeness to heaven!

What was Dareste’s little pile of pebbles next to such a monolith?

Dareste looked down. He felt his face flush. His hands grew clammy and he twisted his robes between them.

The voice echoed around. Dareste knew that voice. He hated it.

His flushed face burned. Damn him! He looked at the tall pillar. It was roughly made, stones piled one on top of the other.

Dareste leaped toward it.

His body collided with the tower, toes clinging onto stones, arms grasping around the circumference, scraping against the rough rock. He held onto the pillar, face pressed against it, panting.

Then he began to climb.

Dareste was not a particularly strong man. Months of sitting on top of a rock, day and night, did not leave one with much muscle. So he was a little surprised to have even made the jump, let alone remain attached to the pillar. Each time he reached up to grab the next stone, he expected his grip to give out. But each time he grasped on and held. His legs shook with exhaustion, but every time he commanded his foot to raise it did.

In this way Dareste climbed the pillar.

He didn’t climb constantly, of course. In fact, practically every movement was followed by an extensive rest. It wasn’t long before he looked down and could no longer see the top of his pillar. Perhaps it had never been there at all. Dareste clung to the side of a stone tower that stretched into the distance in both directions. Up and down. Down and up. Maybe up was west and down was east. Dareste climbed to the west, to Constantinople. He held onto the stones and dragged himself up the road.

At first, Dareste was propelled by anger. It bubbled inside of him. But exhaustion soon depleted it, and the pool ran dry. He kept going nonetheless, the emptiness a far more reliable fuel.

Thoughts sometimes floated across that nothingness. Nothing too complex. Easily addressable. “I need a piss,” followed by emptying his bladder. “I’m tired,” followed by a rest. “I miss Mother.” Followed by…

Sometimes the thoughts were less easy to dismiss. “Why am I climbing this pillar?” That one kept returning. It was annoying. Each time it appeared, Dareste felt like it was actually a different question, but he couldn’t quite see what it actually was. “Why am I climbing?”

The strangest part of that, to Dareste, was how obvious the answer was. If he stopped climbing he would fall.

But the question kept coming back. Dareste couldn’t figure it out. He just kept climbing.

It took him a second to comprehend what was happening when he reached up and felt nothing but air. His hand grasped around, grasping for a rock that wasn’t there. Dareste panicked, expecting to plummet — but no, the pillar was still there. It ended here. He’d reached the top.

Dareste heaved himself up onto the top of the pillar. He collapsed and lay there for a long time. His mind was completely blank. It was all he could do to breathe. Gradually the thoughts returned, and with them came some strength. Eventually, he felt himself able to push up into a seated position.

The top of the pillar, a flat circle of stone roughly six feet across, was empty. Dareste blinked. He was the only one up here.

Dareste stood up and looked around. Yes, he was definitely at the top of the pillar, and most certainly alone. All around him stretched the nothingness. It looked awfully similar to the nothingness down below.

In fact, the top of this pillar also looked exactly like the top of Dareste’s pillar.

Dareste couldn’t see his face, but upon examination his body looked just the same as before, too. His palms and forearms were scraped and bloody. The skin around them leathery, tan, caked in weeks of dust and sweat. He felt his matted hair, the patchy stubble on his face. With his tongue he caressed each tooth, every gap. His dry throat ached. His balls chafed.

“O, Holy Father!” The voice called out from above. Was it any closer than before?

Dareste began to laugh. He’d climbed all that way, and for what? Here he found nobody but himself.

“Father!” The voice called. “I, an Angel, have been sent for you!”

“Wrong person,” Dareste said. His voice came out easily, despite his parched throat.

“What?”

“Wrong person,” Dareste repeated. “You’ve got the wrong person. I think.”

Dareste opened his eyes and was immediately struck with pain. He closed them, but the pain remained. His stomach cramped, throat convulsed, lips stung. He groaned.

“Thank the Lo— oh, you’re awake,” Mother cried, bundling Dareste into a hug. “I thought you were going to die, Dareste.”

Dareste let her hug him, fuss over him. She ladled broth into his mouth, dabbed a moist cloth at his closed eyes, massaged his knotted legs and shoulders. All the while she talked. At first, Dareste only understood fragments. Mother’s voice faded in and out of legibility. It mixed with the background noise. Why was everything so loud? Thuds, shouts, cries of animals, rumbles — too many sounds to comprehend.

After a while, Dareste held up his hand. Mother stopped talking. Dareste tried opening his eyes. He found himself able to see, found himself in a dimly lit room. His Mother’s room. There, sitting next to him, was Mother. She looked down at him, worried. He seemed to be lying on the floor.

“What were you saying?” He asked.

Mother wrung her hands. “What do you remember?” She asked.

“I fell off the pillar,” Dareste said. “No… I climbed down?”

“Oh, Dareste,” Mother said. “You almost died. When we arrived you were too weak to even stand. It’s a miracle—”

“We?” Dareste asked. “Who’s we?”

“You don’t think I carried you back here by myself, do you?” Mother laughed. “You need to put some meat on those bones, but I still couldn’t have managed it myself. Thank God Andronicus came with me.”

“Who?”

“Your savior,” Mother said. “Did you not see him pass by on his way to the city? He told me you spoke. That he was impressed with your learning. He caught my eye in Church. Very handsome, actually.”

“Mother.”

“I can’t speak the truth, now? You want me to lie? Anyway, I asked him about you, and he said he’d spoken to you. He seemed a little concerned. Asked me all kinds of questions. We were together when we heard about that man Samat’s mob. He agreed to come with me.”

“You were together?”

“Yes.”

Dareste found himself unable to protest. “Continue, please.”

Mother raised an eyebrow and grinned. “Now, that’s a sight. You really are sick, aren’t you? My poor Dareste.”

“Mother.”

“Alright. Yes, we heard the mob was coming back out, and I knew something terrible was going to happen. I just knew. And look, we came just in time. Andronicus helped me carry you back — he did most of the carrying, really. We passed by the mob on the road. They didn’t bother us. Actually, some of them even bowed at us, though I can’t figure out why. Madmen. Several of them were carrying that man Samat on a sort of palanquin. They had a bunch of wood, too. I couldn’t figure it out, but Andronicus was muttering under his breath, so I didn’t think it a good time to ask. Besides, he was busy carrying you, and you kept jerking and jostling. He really is a strong one, I’ll tell you that.”

“Stay focused.”

“Sorry. Well, we brought you back here, and I waited for you to wake up.”

“Where is…”

“Andronicus? He left immediately after leaving you here. Seemed very unsettled. I assumed it was about that mob. Or maybe…”

“And?”

“Well…” Mother hesitated. “You might want to sit down for this.”

Dareste stared at her. She grinned.

“I’m just so relieved,” she said, “I can’t help but joke. Not that there’s much to joke about.”

“Mother!”

“OK, OK.”

Mother launched into another tale, and this time Dareste kept his mouth shut. He felt his head swelling by the minute. The mob adding more wood to Samat’s pillar, building it even higher than before. Samat climbing up on top. Bribes to the city to let him continue his extortion of travelers. A mass of dust on the horizon. Great clouds of dust, growing ever larger as the day progressed. Riders appearing, strangely dressed, confronting the mob. An army not far behind. An army of savages, from the south. From the desert. A massacre.

The killing of the mob seemed to have quashed any potential resistance in the city. Then again, it didn’t take a genius to realize it would be difficult to defend a city without any gates. A few incidents of violence here and there. The barbarians stole supplies — they called it resupplying — and moved on fairly quickly. A force of officials and guards remained behind. They were already paying some locals to build a new pair of gates.

“Wait,” Dareste interrupted. “How long have I been asleep?”

“Several days,” Mother said. “I squeezed water and broth into your mouth. You were quiet, mostly, until the end.”

“What did I say?”

“Oh, you didn’t say anything. You just started laughing.”

Dareste shook his head. He’d felt as though he’d been gone for years. And yet his mother looked younger and happier than when he’d left to go up his pillar.

“What about Samat?” he asked.

Mother grimaced. “Can you stand?”

Dareste heaved himself to his feet, leaning heavily on Mother for support. Together, they moved out of the house and into the street. The pair inched along, sticking to the sides to avoid the crowds flowing each way. Mother didn’t complain at how slow Dareste hobbled, or how often he had to stop to catch his breath. Things seemed normal, albeit with an undercurrent of tension.

In fact, Dareste and Mother made their way to the main streets without any issue. Even the central square, in which people moved around vendors selling goods on blankets and in stalls, seemed as usual. Dareste began to wonder if Mother had been joking. Then he saw them.

On the other side of the square, by the archway, stood a small group of people. The crowds gave them space, making them stand out. They were examining the archway where the gates used to be.

Most of the figures in the group were dressed in strange black robes, extending from their necks to their ankles. Two of them had similar black wraps around their heads. The man in the middle was dressed in a similarly flowing wrap, but in a dirty grey wool. He turned and Dareste caught sight of a red, bulbous face, skin peeling. The man’s watery blue eyes met Dareste’s.

Dareste gasped. He knew this man. The priest. But where was his cross? His robes?

The priest looked at Dareste. He seemed to sigh, smile a little, and shrug. Then he turned back to the men with him, apparently having been asked a question.

Mother pulled Dareste away, and he let himself be taken. These people, the invaders, were not Christians. Dareste was sure of that. And yet, there was the priest, wearing their clothing, showing them around.

Dareste ruminated on this as Mother guided him toward the city wall.

“Mother,” Dareste said, “the exit is over there.”

“We’re not allowed to leave right now,” Mother said. “Can you manage the steps?”

Dareste sighed. Mother practically pushed him up the stone steps leading to the top of the wall. He needed a few minutes to sit and gather his breath before stepping up to the edge.

A familiar sight stretched before him. The road, the valley, the horizon. But there, in the near distance, was his pillar. On top of it was a wooden cross, itself twice as high as the stone pillar underneath. It was made of dozens of planks of wood lashed and nailed together. On the cross was Samat.

Signs of violence were evident around the pillar, though any other bodies had been removed. The shadows of circling vultures moved across the ground. Beyond the pillar, a cloud of dust announced travelers approaching or leaving the city. Samat hung in the air, silhouetted in the sunset, in front of this cloud. Blood stained the base of the wooden cross.

Dareste felt strangely empty at the sight. He wasn’t angry, or happy. Mother patted his back. After a while, she suggested they head back home, and Dareste agreed.

Did you figure out which story this is linked to? Get access to all stories, old and forthcoming, by subscribing. It's free.

Member discussion